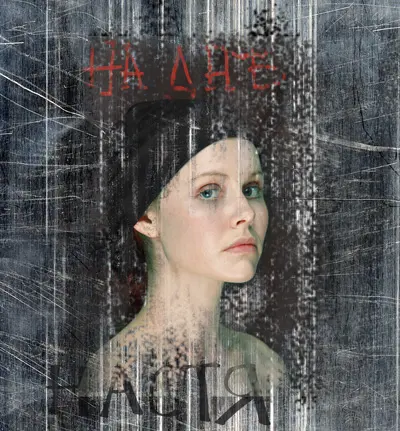

The Lower Depths

THE LOWER DEPTHS is a great play. It is thrilling that a Company of artists would find it important and challenging to give the theatre going public in Melbourne the opportunity to see this text. The Company of artists committed to the production is extremely impressive and boasts of actors of high standing. I recommend that you attend if you can. The production and acting is flawed and very uneven but the play is memorable and ought to be within the repertoire of any discerning audience’s experience.Young audiences and students of the theatre, this is a must for you to witness. Here, is a rarely seen, in Australia, important part of your dramatic heritage.

THE LOWER DEPTHS by Maxim Gorky is a great play. It was written for the Moscow Arts Theatre then at the height of its gestation under the artistic inspiration of Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Dantchenko. It was first performed in 1902 to great acclaim and success. Gorky a young man brought up in the urban underclass of Russian society has recorded his life in a famous autobiographic trilogy: MY CHILDHOOD; MY YOUTH; MY UNIVERSITY. (The Russian films of the trilogy are also fabulous.) The world of this play comes directly from a life well and intensely lived and observed in economic struggle end turmoil.

Gorky had through Chekhov befriended the Moscow Arts Theatre company and he wrote with a close knowledge of the actors and their abilities. Stanislavski and his company had been developing their approach to acting style for some time culminating with Chekhov’s THREE SISTERS in 1901. The Ensemble acting for which this company became famous, and the western theatre has tried to emulate since, was at its most complex. One of Stanislavski’s famous maxims is “That there are no small roles, only small actors.” This great text of THE LOWER DEPTHS is proof of that. 16 roles where there is no leading character. All of the roles need to be equally present. This play has no real plot. It is rather a close observation of a collection of down and outs attempting to survive in a boarding house/doss house in the suburbs of a city. It requires, to succeed, a group of actors, fine tuned individually, and to each other as an ensemble.

The play demands actors that are in the most felicitous place with their technical skills. Body, Voice, Intellectual and Emotional skills. The soloists or the instruments in the company or “orchestra” need to be at top of their form. And most importantly they need to be fully attuned to each other. It is interesting for me to reflect on some of my recent concert going experiences in relation to what I believe the Gorky play requires. The genius of the AUSTRALIAN CHAMBER ORCHESTRA especially under the direction of Richard Tognetti is the ability for each of these gifted individuals to subsume their skills into a flawless ensemble to serve the music. Again, sitting in the Hamer Concert Hall, high up in the Balcony, last Friday, listening to the MELBOURNE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA play the Mahler Ten, one could see the ensemble of an enormous orchestra serving collectively the score on the page to rewarding affects. The great skill of the individuals serving the whole, the ensemble.

So the problem with this production for me is that the company of actors appear to be uneven in their primed skill areas. The director (Ariette Taylor) does not seem to have solved the style that the work will play in. There is an uncomfortable clash of approach from the actors. Some seem to be playing a kind of documentary reality, where the voice work seems to be unsupported and mistakenly real. Others are playing at a vocally thrilling pitch of “theatrical reality”. This is true of the physical commitments as well. There is no consistent play style. The ensemble style is too diverse. My best experience came from some of the smaller roles: Adam Pierzchalski (Alyoshka); Evan Jureidini (Tartar); no small parts indeed! Their ensemble presence adding a life force that extended not just to the playing area but also to where they went in the bigger world of the play when they left the stage. On stage they were living a life, not enacting a scene. Greg Stone (the Actor) was mostly magnificent, playing an artist who has self destructed under the tragedy of alcoholic addiction and paying the ultimate cost, suicide. Marco Chiappi (The Baron), whom I have never seen before, gave a marvellously calibrated performance of a “fallen man” – a vocal timbre, physical habitation and a set of intellectual interpretative choices that were spellbinding to behold. The courage of the performance was knife edge in action. Alex Menglet (Luka) gave promise of greatness, but needed more skillful assistance from the director to vary his approach. It lacked shape. It appeared to be conceptualised rather than experienced. Physically and vocally owned, the range of expression was too limited to maintain interest to this enigmatic character. This great mysterious character of dramatic literature, Luka.

The biggest difficulty for me was the work of Stewart Morrit in the pivotal role of Vaska. He appeared to me to be playing all to himself. The text was elocuted – seemingly “sung” for affect rather than the pursuit of an objective or even to tell a story. It appeared to be self affecting and presentational. The story he was telling was secondary to the emotional life. Sentimentality was the principal colour. No matter which scene he was playing in, the other characters were only serving his emotional journey. It was the antipathy of what the play requires. Vaska deals with a lot of the people in the house and is the well spring of the narrative melodrama. It was hard to follow the story as each of these 16 characters have contributions which must be played and placed firmly in focus, for the whole to make a satisfactory experience. The role that every actor has is absolutely integral for the play to have an impact. This could only happen if all the actors were dealing with each other. I felt Mr Morritt was not doing so and he dealt with a large number of the characters. The Act three duet between Chloe Armstrong (Natasha) came to a stand still as both actors tried to out act each other with the emotional truthfulness, forgetting the story and disengaging me from the plight of the characters. This was like looking at separate parts, I was asked to watch his acting instead of been asked to chase the story and endow the performance and story with my emotional truths which he should have been inspiring me to do. I was not to have a catharsis, I was been asked to admire Mr Morritt’s catharsis. That is not good theatre.

The other actors in the ensemble were uneven in their energy commitments and seemed to come and go. All of the actors are capable, but last night, when I saw the performance, not in tune with each other and inconsistent in style. Syd Brisbane had physical energy but diffident vocal energy. Mr English waited for his turn in the fourth act to make an impression. Prior to that he was less engaged and not earning his place in the sun. Genevieve Picot, whom I thought was brilliant in ROCK AND ROLL earlier this year, seemed unable to get a grasp of Anna. The illness was not convincing nor was the textual contribution.

The Design, both set and especially costume, by Adrienne Chisolm made wonderful use of the space and was well served by Emma Valente’s lighting design. The sound design was minimal but the use of the live accordion and the music and lyrics by Adam Pierzchalski and Greg Stone were especially evocative to the creation of the world. The Act two scene change had a charge that was quite thrilling as did the final act song that led us to the final startling moment of the play (The theatrical disturbance in the roof of the actual space at the end of Act one was truly galvanising for its veracity.).

The translation which seems to have had much care and contribution from all the artists, was adequate, but may have been to personalized to the actors at hand and so seemed less striking or less managed poetically, as some others I know. Gorky is relatively difficult to manage, as his observation of life is full of repetitions and ellipses that may in a less romantic culture be too slow to play. It takes courage to risk boring an audience. But if you don’t have the courage, you may lose the authenticity of the writer and the world of the play. I felt it was interesting at the Sydney Festival two years ago when a Russian company performed UNCLE VANYA, the running time was almost four hours. Most agreed it was superlative Chehov. But culturally most Australian productions of Vanya run in at about two and half hours. We generally fear we might bore the audience. What greatness may be in the repeats and ellipses? (Have you seen an uncut LONG DAY’S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT? or an uncut PEER GYNT? I have. There is a wonderous dramatic difference to the dramatic literature as live performance when respected in this way.) This Gorky played on Saturday night less than three hours and here I think maybe part of the problem.

I never saw the Ivanov production by Ariette Taylor and most of this company of actors, lovingly remembered throughout the notes of this production’s program. This Gorky work has evaded this company. The director has a choreographer’s eye for beautiful stage pictures but not enough of a steady textual hand to guide her actors through the music of the play. There is a tendency towards romaticising the Russian world as well. And this world of shocking poverty is not in the least romantic. A read of Orlando Figes NATASHA’S DANCE and/or A PEOPLE’S TRAGEDY will enlighten one away from such inclinations about the Russian dilemma at the beginning of the last century. Interesting it is to read on page three of Saturday’s The Age newspaper of the plight of duped international students ending up destitute and living under a bridge near the Rod Laver Arena in our own time to see the relevance of this play. IVANOV is a relatively minor play that can, because of its flaws, still interpretatively surprise. It also has a relatively simple melodramatic structure, that allows for actors to indulge their feelings more individually than play more disciplingly objectively to the score written on the page for an attuned ensemble. It allows, relatively, for a romantic or sentimentalised indulgence of the Russian world. THE LOWER DEPTHS is a much more formidable masterpiece of reality and of ensemble theatre and needs more respect and/or time to bring to fruition.

Gorky gains in reputation as time passes. SUMMERFOLK, ENEMIES, THE PHILISTINES, THE CHILDREN OF THE SUN are quietly making appearances on the world stages. Chekhov wrote with a sense of his own impending doom. Gorky wrote with the hope of a better future. A better economic justice. He, despite attempts of suicide was a very robust individual. I always wondered what Chekhov would have gone on to write for the theatre had he lived on into the revolution. May be this company could look at Bulgakov. I would come to see that as well.

Congratulations on the vision and dedication to all these artists for the commitment to toil over this work.