Hamlet

Belvoir presents HAMLET by William Shakespeare in the Upstairs Theatre, Belvoir St, Surry Hiills.

HAMLET by William Shakespeare, is, perhaps the challenge, the equivalent measuring stick for a theatre company and its artistic endeavours as, say, Tchaikovsky’s SWAN LAKE may be for the Ballet Companies of the World, or, Wagner’s DE RING DES NIBELUNGEN may be for an Opera Company, or, Beethoven’s NINTH SYMPHONY for a Concert Orchestra.

This production of HAMLET at the Belvoir Theatre is an adaptation by Simon Stone of William Shakespeare’s play, for 8 actors and 2 musicians. The original text has been severely edited and re-arranged.

“Hamlet is a play that, probably, has been performed more than any other play in the world, and been written about, more than any other literary work. It’s been translated more than any other play and has inspired more spoofs” – the Nimrod St Theatre (the ‘father’ to Belvoir St Theatre) back in December, 1971 gave a Christmas pantomime called HAMLET ON ICE by Michael Boddy, Marcus Cooney, Ron Blair, and the cast: one of the many famous moments included Kate Fitzpatrick as Hamlet, contemplating a spectacularly ‘shelved’ part of her body while uttering: ‘O, that this too too solid flesh would melt, thaw, and resolve itself into a dew!’ – “spinoffs, offshoots, send ups, burlesques, and adaptations, including a spaghetti western called JOHHNY HAMLET and a four minute cartoon, ENTER HAMLET, narrated by Maurice Evans. There is even a Popeye version of the play,” and I am sure I can be pointed to the Simpsons episode (episodes) dealing with this Prince of Denmark. “There have been more than fifty film versions of this play” – the Rory Kinnear, National Theatre production (2010) is soon to be re-screened as part of that Company’s 50th Anniversary celebrations here in Sydney – weekend 30th Nov-1st Dec. Benedict Cumberbatch is next actor off the rank, in London, I’ve heard!) “It has inspired, twenty six ballets, six operas, and dozens of musical works from Tchaikovsky and Listz to Shostakovitch to contemporary composers. There have been Hamlet cigars, bicycles, beer and laundry mats, Hamlet jewellery, games, paper dolls, and maps of the world abound with towns, streets, and business establishments called Hamlet.” (1.)

HAMLET is rarely performed in its entirety, it is the longest play Shakespeare wrote. The uncut version, dubbed the “eternity Hamlet” by critic John Trewin, takes four and a half to five hours to perform. The Kenneth Branagh film version (1996) is just over four hours long (although, there is also a two and a half hour edit). Mr Stone’s version is some two hours twenty minutes, with an interval. Truncated, indeed.

The interview of Mr Stone given to Ralph Myers, the Designer of the production, and Artistic Director of Belvoir Theatre, in the program notes to this production, reveals to us that Mr Stone was drawn to this play for three reasons: “Because it’s an amazing play” (not all of it, “amazing” enough it seems), that he has found the right (timely) actor for it, Toby Schmitz (and one assumes, also, sub-sequentially, Ewen Leslie!) and, thirdly, that he has a particular personal connection to it, the loss of his own father when he was a boy:

All of the plays that I want to do have some resonance with the life that I have lived – necessarily, because you don’t respond to something if you don’t recognise the motivations of the characters in it, or the world. The experience of having lost my father colours MY version of Hamlet, rather than just the choice to do it.

Of the emphasis in the adaptation and production of this HAMLET, Mr Stone tells us:

It’s about following the path of a grief-addled brain into complete self-destruction. … This production of HAMLET reflects, in certain ways, that experience of mine. … That’s the reason why the HAMLET story (or, at least, the one Mr Stone has edited for us) unfolds as it does. Because he’s not only someone who misses his father and wants to see him, but he’s also ready to attack the world and try to reshape it in the image of justice that he believes in. And so it’s a really tragic combination of a newly ideological man and a sense of righteous grief. It helps us to understand his need to take vengeance.”(2)

This psychological shadow that this artist, Mr Stone, freely, tells us of, then, has had other therapeutic exercises for us at Belvoir from this director, as I recall. Just consider the obvious ones as in Arthur Miller’s, DEATH OF A SALESMAN, with its core relationship (and climatic scene) between Willy and his son Biff; that of Brick and ‘Big’ Daddy, especially in the long Act Two duologue between them, in Tennessee Williams’ CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF. One can stretch it further, perhaps, into the core of THE ONLY CHILD; THE WILD DUCK, both adaptations of Ibsen texts, both, with child and parent issues in its dramaturgical structures; and the Eugene O’Neill, STRANGE INTERLUDE, other Belvoir productions of Mr Stone’s. One has been waiting for Mr Stone’s ‘go’ at HAMLET to see how this dominating thematic of his would manifest.

Richard Eyre talking of Hamlet:

His father dies suddenly, cut off in his prime. His mother marries within two months. Now I challenge anybody who’s very young and sensitive and imaginative not to feel the chronic grief and the most chronic emotional disturbance as a consequence of those two things. And anybody who disputes that simply has never experienced any kind of jealousy or disturbance concerning the sexuality of their parents.” (1).

This Hamlet’s attack on the world about him, in Mr Stone’s edition of the core text, focuses the incredible vulnerability of a son who misses his father, by emphasising the psychopathic nature of Hamlet under these due pressures, concluding with the visualised staging of the walking dead, all dripping blood – innocent bystanders killed in his rage for justice (Ophelia, Laertes, Polonius, Rosencrantz/Guilenstern, Gertrude, and the not so innocent, Claudius) – and in his vituperative misogynistic treatment of the women, Ophelia (the Nunnery scene), and Gertrude (the Closet scene). It is a powerful diminution of Shakespeare’s great play to serve this Adaptor/Director’s purpose. Striking and convincing, but, only, on its own terms, for Shakespeare’s HAMLET is so much more than that of Mr Stone’s vivid experiencing of his own life and world, it seems, from the extant evidence of this production.

Sitting in a black curtained, flat-black floor space, (Set Design, Ralph Myers) as the audience enters, is a pianist (Luke Byrne), dressed in concert tails (Costume Designer, Mel Page) at a black grand piano, playing softly, maybe, some Satie (- just briefly, wickedly, I had hoped for some Coward!) A set of black chairs line the walls. Rows of cylinder lighting-focuses, hang down from the roof (Lighting Design, Benjamin Cisterne). Toby Schmitz, in a dark velvet lounge jacket and dark pants, coiffed meticulously, sits and listens, and watches us enter; occasionally, drawing our attention to another seated figure on the other wall, in a white linen suit coat and light coloured trousers with an open necked white shirt, Anthony Phelan. Mr Stone, in the present-life as we enter, thus, introduces us to a young man, presumably, Hamlet, communing in silence with another, presumably, the ghost of his father (for me, this imagery, and the always present inter-actions between these two, during the production, evoked the imagery from Ingmar Bergman’s biographical film FANNY AND ALEXANDER – 1982), and just as Mr Stone, in life did, (he confesses in the notes of the program), they interact ” … in waking life, meeting with him and talking to him and living with him” so that this very personal direction, production, “reflects … that experience of mine.” (2). The light dims in the auditorium and a counter-tenor (Maximilian Riebl) wanders into the space singing, creating an ethereal mood/atmosphere with the first of many songs from a repertoire of, mostly, seventeenth and eighteenth century sound – the last being the famous, “When I am Laid in Earth” – Purcell, DIDO AND AENEAS, (a la Kosky).

A company of actors, then (they have no exclusive definition in the program, just their name listed as a company), act out, role play, recognisable, speeches that demarcate them as characters from Shakespeare’s play: Toby Schmitz=Hamlet; Anthony Phelan=the dead King Hamlet; Thomas Campbell=Laertes; Emily Barclay=Ophelia; Greg Stone=Polonius; Robyn Nevin=Gertrude; John Gaden=Claudius and Nathan Lovejoy=Rosencratz/Guildenstern; but, they also, seamlessly, take on responsibility of edits and conglomerations of other characters/speeches (e.g. Horatio, the Gravedigger, Osric, Fortinbras) that smoothly facilitate this therapeutic-exercise of Mr Stone’s. For those of us who know the play well, it is a fascinating exercise to unravel and interpret this new twisting ‘plot’ from the original play; sorting, intellectually, the staging of this exercise, which is an imaginative concoction of invention, to serve the peculiar, particular “possession”, by Mr Stone of this great play – it, being well and truly out of copyright jurisdiction, unlike the recent American texts employed by Mr Stone, it is a rewarding and malleable resource, indeed, to appropriate for this explorative exercise. After the interval we return to the theatre that now houses, not unexpectedly,(some of us won and lost a bet!), a white-hot box, with piano etc as before, but, with an actor in a large pool of blood, it, too, not an unexpected design or directorial gesture (again money changed hands). It is, undoubtedly, true, the whiter, the brighter the box, all the better to see the drips, foot and hand prints of the victims trailing over the ‘canvas’ of the design, to illustrate the mounting deeds of unhinged Hamlet. The design of this production, essentially is a familiar technique, such that the effect is not really much of a palpable theatrical ‘hit’ these days- over usage has worn-out the impact of its ‘plotting’. The costumes are very reminiscent of the Philip Prowse,1970-80’s Glasgow Citizens shock and awe look – again, a not too unfamiliar offer.

The acting is the thing here. The bristling intelligence and intelligibility of these performers lift this convoluted production into a must watch intensity – they indicate to us, that they are in control of every minute of the director’s demands and so arrest our attention, rivet us, defy us to not to engage. Could there be a more powerful, creative group onstage, together, this year so far? Thomas Campbell, Nathan Lovejoy, Robyn Nevin, Anthony Phelan, Greg Stone, John Gaden, Emily Barclay and Toby Schmitz? The cleverness of communicated intention and craftsmanship is of a very high order. It is, also, an ensemble of much empathetic force. “What might this group of actors have brought to Shakespeare’s play, as written, as well?”, one wonders.

Anthony Phelan, with not much text, creates a radiating force of presence, dominating the atmospherics of this production with an imperturbable self-possession of pity. Nathan Lovejoy, too, creates with his non-verbal ‘acting’ in response to what is happening about him, a clear and insightful commentary to the dilemma that Hamlet’s behaviour has made – the relaxed presence brings a maturity to his human tasks, both mordant and tragic (see, EMPIRE: TERROR ON THE HIGH SEAS), and although, relatively, verbally textually, limited, he is, of course, no slouch in delivery. Thomas Campbell confirms, further, to remarkable effect, his ability to balance objective craft technique and subjective expression of emotion to tell his story in the jigsaw of this production, (see PENELOPE) – his ‘dealing’ with Laertes’ grief, in the later scenes of this production, brought a humanity to this production which otherwise tended towards a favoured, a cooler cerebral set of choices.

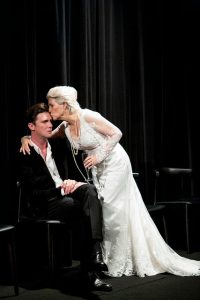

Robyn Nevin’s Gertrude, structures a narrative journey of a woman ‘drinking’ herself into a kind of oblivion to blind herself to what she suspects and what she knows. There is a sense of the ‘whitened sepulchre’ in her offers – dressed in an elegant, trained-white dress, topped with a strident white haired coiffure that progressively deteriorates into a look of frenzied chaos – almost never without a glass in her hand, the irony of the poisoned chalice becoming the agent of her demise, is cleverly underlined. (That Mr Stone has Ophelia walk, resurrected and wet, across the stage during Gertrude’s, telling of the suicide of Ophelia – “There is a willow that grows aslant…” Act V Sc 1 – does no favour to Ms Nevin’s performance of it -splitting our focus.)

Greg Stone as Polonius seems to have most of his original text in place and he makes the most conventional postures in this company, confidently amusing and befuddled – aiming directly for the ‘low comedy’ of it; while John Gaden seems surprised to be creating Claudius, his natural demeanour and usual work reflecting more the dithering intellectualisms of Polonius – I wondered if the actors had changed roles, what would have been the consequential dynamics? Certainly, one was a little bewildered with the physical age of Mr Gaden’s nefarious man, certainly in the character’s objectives towards Gertrude and the Kingship (perhaps, like our Prince Charles, Claudius had become too tired of waiting!)

Emily Barclay was the surprise, for me, Ophelia’s early scenes had a simple and uncomplicated clarity and gave us room for empathy, although the famous, later, ‘mad’ scene, was the usual straightforward reading, this singular re-writing of the Shakespearean original by Mr Stone, not able to give her, or, us, a new viewpoint – it is a notorious difficulty (one wonders why actors more often than not, want to solve Ophelia), and here the relatively uncut length seemed to hold-up the impetus to the production’s climax.

Toby Schmitz, has played Hamlet before, and he brings to this cut-up version, the confidence of a pre-knowledge, a knowing of what is not there any more, and embodying that Shakespearean absence with tremendous madness in craft, equally measured, accompanied, with his intelligence, even as he demonstrates, once again, an unchecked tendency to indulge the role and its potential filled moments (see ROSENCRANTZ AND GUILDENSTERN ARE DEAD) – pushing his affects. One did wonder, if Mr Schmitz with his inventive and often playfully wicked sense of humour -noted the skips over the puddle of blood – nearly always on display in his performances, was also parodying Mr Stone, by investing this Hamlet with such a broadly ostentatious Australian accent – one that ‘was weary, stale, and especially, flat in its vowel exaggerations. From the get-up, even when sitting against the wall, in the audience entrance prologue, the performance is emotionally super-charged, pitched at a passion that he seems to tear to shreds, threads, later, flushing almost permanently crimson with effort, with the veins of his neck attempting to break through his skin to spurt us into this Hamlet’s grief and rage – a rage, that in the production’s final conceit of the walking, dripping-blood dead, surrounding him – focuses on the psychopathic violence of a late Elizabethan world. In summary, a fine but partial Hamlet. Not enough soul, perhaps. How fortunate that Mr Stone, the director, has found the therapy of practicing in the field of the performing arts to overcome his own contemporary life experience, for good, rather than destruction, then!

I enjoyed myself with the cryptic un-doing that I had to bring to comprehending this ‘take’ on Shakespeare’s HAMLET. My knowledge of the original was a decided asset.

Mr Stone, defending his interviewer’s, Mr Myers’, assumption that most of the audience would know the play, believes, that even

People who have never read or seen the play before should be able to have an entirely enjoyable experience, understanding what’s going on and be transported by it.

This was not the case, of course, for everybody, and some of my companions, with no experience of the original play, or, only a cursory one, found themselves lost and frustrated in trying to comprehend who was who, and what was happening. So bewildered were they that they found their only re-action to the last scene’s conceit of the walking, choking gurgling dead – “Hamlet and His Zombies’ Haunting”, some of them delightedly called it, after – was giggling at the stylised choices, not anchored, for them, in any recognisable form, or clear storytelling technique to comprehend, at all.

I had recently watched, with some of them, the Marvel (Comic) Studios, THOR: THE DARK WORLD (2013). I had not seen the first film and so found that I could not grasp, for some time, who was who, and how they were related, and what was happening and why. My companions did not find, like I did with THOR at the Events Cinema, a secure understanding and transportation in the Belvoir theatre of this version of HAMLET. This HAMLET is a Reader’s Digest version of the original, with Marvel Comic like actions, claiming some of the material to serve to tell what has been textually removed, to attempt to clarify for the audience this very personal life recognition of Mr Stone’s in the late career of Hamlet (the five acts of Shakespeare’s play.) The audience communication is limited and although, like THOR it has some directorial whiz-bangery going on, it seems to ignore the general audience and assumes a kind of elitist expectation of literate sophistication from all of them. Mr Stone tells us that his reasons for “omitting bits” of the play, and, although he mourns the loss of sometimes famous, even plainly insightful lines:

“…my philosophy is that if you are listening to a lot of the play means you stop listening to the really important scenes then you have done a disservice to the whole. The aim is always that the audience listens to every single word of the play put on stage. In every production you achieve that by making choices.” (2).

Unfortunately, some of the audience were not able and, or, could not, did not listen to all of the words of even this self-serving edit of the original, and stopped listening. Mr Stone’s generous aim in re-creating HAMLET, so that we may hear all of the text, he thought important, was then, a disservice to the parts of his construction (destruction), as well as to the whole of Shakespeare’s original.

“In the tragedy of HAMLET, the ghost of a king appears on the stage. Hamlet becomes crazy in the second act and his mistress becomes crazy in the third. The Prince slays the father of his mistress on the pre tense of killing a rat, the heroine throws herself into a river. In the meanwhile another of the actors conquers Poland. Hamlet, his mother and his father carouse on the stage. Songs are sung at table. There’s quarrelling, fighting, killing. It is a vulgar and barbarous drama which would not be tolerated by the vilest populace of France or Italy. One would imagine this piece to be the work of a drunken savage.”

So says Voltaire of the original. I wonder what he would make of Mr Stone’s HAMLET, it, using only some parts of Shakespeare’s play.

This textual adaptation of Shakespeare’s play by Simon Stone was a disappointment, redeemed by acting of dazzling concentration and commitment, although one was never much moved, mostly, just cryptically stimulated – it was fun decoding the staging of the edited original. As far as the production of HAMLET being a bench mark of excellence for a theatre company, I estimate it a failure, (see, Hamlet***).

P.S. One had wondered with real interest what Mr Stone would have made of Philip Barry’s 1939 comedy,THE PHILADELPHIA STORY, its actions and themes so, unusually, outside his usual display of interest – a young woman conflicted about her marriage choices. Alas, we will never know, as the rights for this announced production for the coming Belvoir subscription season, have not been granted by its owners. Instead, we shall have Mr Stone’s response to the “resonance with the life that (he) has lived” concerning Gogol’s classic satire of a presentable young man, Khlestakov, who face to face with a community willingly accepts a persona thrust upon him by that deluded community, showering him with gifts, defrauding them sufficiently to leave town laden with loot: THE GOVERNMENT INSPECTOR. I look forward to it. The well remembered production by Neil Armfield is well treasured.

- The Friendly Shakespeare – Norrie Epstein. Penguin Books – 1993.

- The program notes from the Belvoir program for HAMLET.

1 replies to “Hamlet”

Just a minor correction – Neil Armfield never directed Government Inspector for Belvoir. He did it for the Sydney Theatre Company (with a lot of collaborators who normally did Belvoir shows with him).

Comments are closed.