ACO tour Six: Viennese Serenade

Australian Chamber Orchestra (ACO) present Tour Six: VIENNESE SERENADE with Benjamin Schmid in the Concert Hall, the Sydney Opera House.

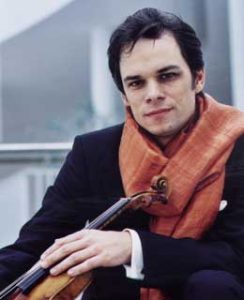

Benjamin Schmid acting as Guest Director & Lead Violinist with the Australian Chamber Orchestra presented a delightful concert, mostly focused on the Viennese influence on the music experience. What is nearly always joyful about the guest artists that the ACO invite to work with them, is the calibre and musical love that these artists bring to their work. What was most affecting for me was to see this relatively, modest looking artist appear with the orchestra, (firstly in a sedate soft grey, shiny jacket and then a neat white one) and see him shift-shape into a ‘possessed’ artist, rippling and glowing from within with a passion and conviction for the program he had chosen and then executed for us. That he was Viennese was self evident and the pleasure that he had in revealing and playing this music with this orchestra was translated and given as a joyous gift to us, the audience.

The selection of music began with nothing at all Viennese but a warm-up, utilising the Bach Concerto in D minor for two violins, BWV 1043 (composed c. 1720) with Helena Rathbone, Principal Second Violin of the ACO. Most enjoyable. Relaxing.

To follow was a revelation: a performance of Erich Korngold’s Lento Religioso (from Symphonic Serenade). I know Erich Korngold mostly from his scores for Hollywood films, especially the rousing music for the 1939 Errol Flynn vehicle, THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD. An iconic score that still thrills and certainly holds that film in a land of contemporary thrall. The Korngold score being the essential ingredient to the film’s timelessness in my experience. Great.

The Symphonic Serenade for string orchestra, Op.39, was composed in 1947, after the War in Europe, and grows in reputation amongst audiences and artists as time passes, apparently. The Lento Religioso has a quiet ethereal entrance and the sublime delicacies of the piece held one enraptured and are, still, a week or so after the event, hauntingly present in my consciousness. Mr Schmid then introduced us to a contemporary Viennese composer H K Gruber with his Nebelsteinmusik (composed 1988). In four movements this work was not always able to hold my concentration.

After the interval break, Mr Schmid, on micro-phone welcomed us to the concert and introduced the music to follow. His obvious delighted relish of what he was to give us shone through. Firstly, Rondo in A major for violin and strings, D.438 by Franz Schumann (composed in 1816) – a work that is easy for an audience to enjoy and a pleasure to see the demands made upon the violinist soloist’s virtuosity. The music had a sense of gravity to begin and then slides off to ‘adventures’. The virtuosity seemed to be tossed off with what looked like effortlessness. Vienna was being evoked.

What followed was two short works by Joseph Lanner: Die Romantiker (the Romantics), Op.167 and Die Werber (the Suitors), Op.103. “Lanner’s waltzes … are fine examples of the beautiful late work of the composer who, more than any other (even Johann Strauss II), can be said to have invented the Viennese waltz.” The human response to the waltz rhythm is so deliciously seductive and the smiles that it elicited around me in the Concert Hall were sublimely proof of that. They mirrored the smile and lifting eye brow of Mr Schmid as he exquisitely guided us through the music (eat your heart out, I reflected on Andre Rieu’s concerts.)

To finish, Mr Schmid took us to contemporary Vienna and introduced us to a regular collaborator of his, Georg Breinschmid – “a classically trained double bass player who now works exclusively as a jazz musician, with an increasing reputation as a composer.” Musette pour Elisabeth (composed 2008) and Wien bleibt Krk (composed 2008) were the two works we heard. That in the clever music we heard quotes from the more famous Viennese waltzes brought delight and outright laughter of pleasure from the audience. The music was both contemporary and yet flattering to it’s heritage, a respect that was palpable and highly appreciated by the audience around us.

It is typical of an ACO concert to cover such a range of musical history in one concert. To begin with a Bach composition of 1720 – a work composed before Captain Cook mapped the east coast of our nation – and to finish, with stops along the way, in 2008, with two vitally new works from Vienna, is a treat of intellectual rigour and pleasure that enlarges my perspective of music as a cultural entertainment constantly renewing itself with respect and honour of its past genius. Renewal with a sense of the great shoulders, the new musicians stand on to continue to create – no sense with this orchestra of shunning the past or the present and future, but rather an admirable inclusive love of all of music and its forms as a part of man’s language – past and present.

An orchestra and concert to celebrate.